The controversial world of gene editing just broke new ground by having its first experiment conducted within the U.S. and by significantly increasing the process’ effectiveness.

Whereas China has enjoyed a head start in the field, this new study was performed by a team of researchers in Portland, Oregon.

“So far as I know this will be the first study reported in the U.S.,” said Jun Wu who was involved in the project.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov and his team from the Oregon Health and Science University used the burgeoning CRISPR technique to not only perform the experiment on American soil, but to also expand the process in important ways.

First, they used more embryos than believed to be used in prior experiments.

And second, it’s believed they have corrected many of the errors and shortcomings plaguing CRISPR for years now.

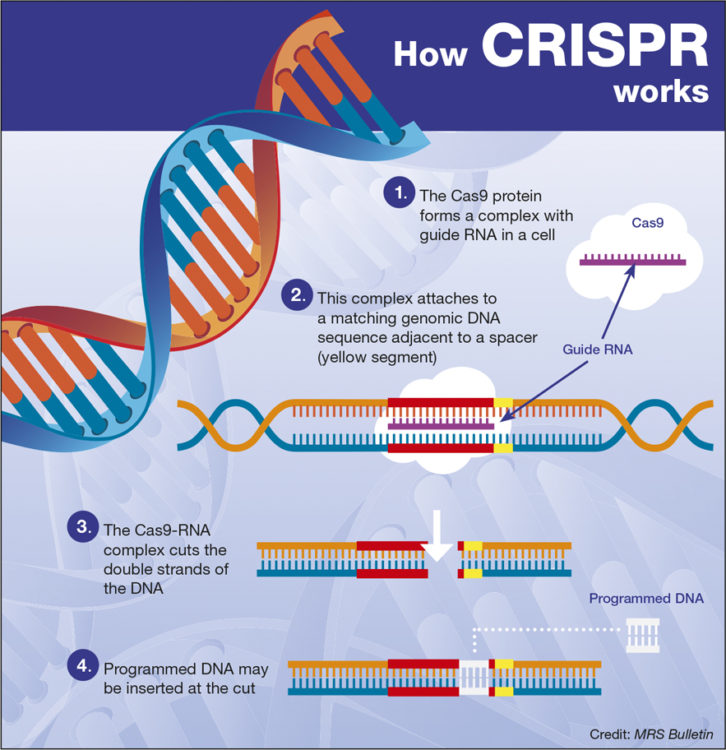

CRISPR, which stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, is a groundbreaking technique for editing human genes in early stages, essentially allowing scientists the capacity to create genetically engineered babies.

Drawing inevitable criticism from religious and human rights groups, CRISPR nonetheless faced the much greater obstacle of only managing to alter some of an embryo’s cells.

Otherwise known as “mosaicism”, the technique’s shortcoming led many critics to the conclusion that it was unsafe for use on humans.

However, Mitalipov’s team used a new, promising approach.

“It is proof of principle that it can work,” said one scientist close to the project, “They significantly reduced mosaicism. I don’t think it’s the start of clinical trials yet, but it does take it further than anyone has before.”

It is believed that CRISPR’s prior limitations were overcome by injecting the gene-editing chemicals at the earliest possible stage—right at the moment the sperm enters the egg.

A mutation causing a heritable heart condition has been corrected in preimplantation human embryos using CRISPR–Cas9 https://t.co/cbE6rYVUwT pic.twitter.com/ASQFd6dViI

— Nature Portfolio (@NaturePortfolio) August 2, 2017

Genetically engineering humans remains a topic of major debate, especially when it comes to ethical concerns.

“Genome editing to enhance traits or abilities beyond ordinary health raises concerns about whether the benefits can outweigh the risks, and about fairness if available only to some people,” said Alta Charo from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Indeed, despite the progress made, Mitalipov did not allow the embryo to develop past a few days—a sober decision given the technique’s uncharted territory.

Source:

Technology Review